Windswept isn’t only enjoyable and enriching; it contains some of the most striking descriptions of nature I’ve ever read.

Horatio Clare – review in The Telegraph

“I have read and read pages and pages of this wonderful book, swept away by its beauty and understanding, its chromatic brilliance, flickering and surging into colour at every turn, moulded to its mountains and all the subtleties of its winds and skies.”

— Adam Nicolson

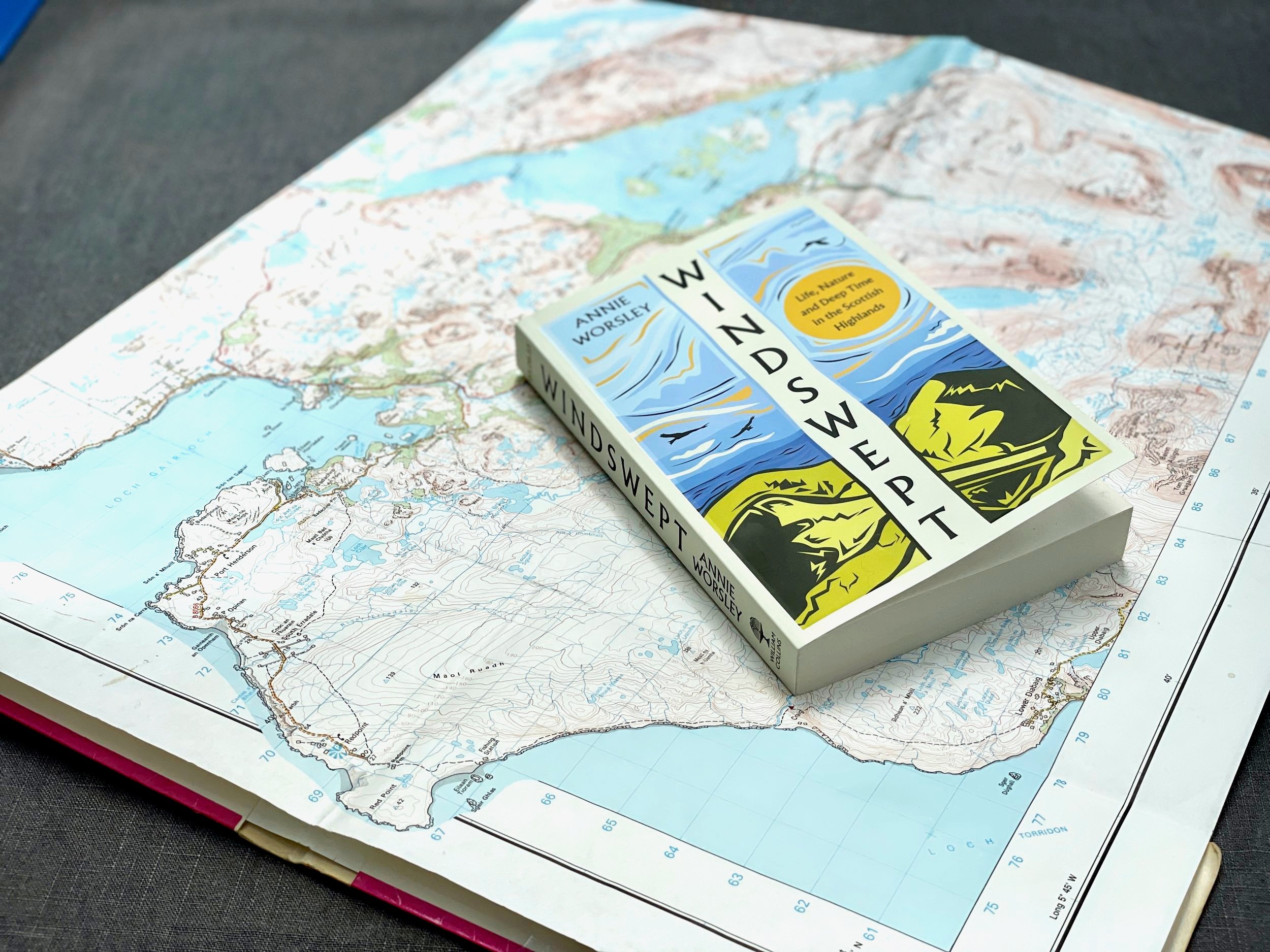

Annie Worsley traded a busy life in academia to take on a croft, or small holding, on the west coast of Scotland. It is a land ruled by great elemental forces – light, wind and water – that hold sway over how land forms, where the sea sits and what grows. Windswept explores what it means to live in this rugged, awe-inspiring place of unquenchable spirit and wild weather.

Walk with Annie as she lays quartz stones in the river to reflect the moonlight and attract salmon, as she watches otters play tag across the beach, as she is awoken by the feral bellowing of stags. Travel back in time to the epic story of how Scotland’s valleys were carved by glaciers, rivers scythed paths through mountains, how the earliest people found a way of life in the Highlands – and how she then found a home there millennia later.

With stunning imagery and lyrical prose, Windswept evokes a place where nature reigns supreme and humans must learn to adapt. It is her paean to a beloved place, one richer with colour, sound and life than perhaps anywhere else in the UK.

Windswept is a wonderful work, prose-painted in bold, bright strokes like a Scottish Colourist's canvas. It is a story of learning to keep time differently, in one of the most spectacular landscapes in Britain. Annie Worsley has written a gorgeous almanac or year-book in which the minutes, hours and months are marked not by the tick of clock-hands but weather-fronts, bird migrations and plant-patterns of growth and decay.

— Robert Macfarlane

An Extract

From Part 4: Summer Solstice to Autumn Equinox

‘As summer progresses and the wildflowers begin to set seed, the grasses produce their flowers in an array of shapes and forms. Their colours are much more subtle – pale peach, russet, cream and yellow – but their delicate nodding heads, or bracts like zippers or tufts and braids, are beautiful and distinctive. The perfume is delicious and overpowers the scent of myrtle from surrounding bogland or saltiness and ozone from the sea. And when the wind blows, the meadows whisper in gentle sounds made by dozens of different types of stem and leaf all moving together. In drier areas the last patches of yellow rattle live up to the name. Its seed pods are percussion instruments played by the breezes. The whole croft fills with drumming and tapping and humming and shushing. Each plant has a unique way of dancing to the wind – some sway or gently wave, others click and jerk. The overall effect is of one great organism rippling and oscillating and singing. There is a phrase, ‘a sea of grass’. It describes almost what a mature meadow feels like: a living organic entity, a single inland sea ruled by the same physical laws as the ocean.

Inside, the structure of the meadow is reminiscent of a rainforest. There are tall stems that resemble tree trunks; creepers and climbers; there are big leaves and decomposing vegetable matter; there are seeds dropping and insects leaping or flitting from plant to plant. It is warm, moist, dark and fecund. The canopy is bright and colourful, flickering with emerging insects. There is an internal sound too, almost out of reach yet definitely present, one that can only be heard by kneeling or lying down among the blooms, a strange crackling overriding the sounds of seeds and clicking stems. Together, all these sounds are the tunes of life and earth, light and scent in miniature, the interconnectedness of living things made manifest.’